Speaking to a packed hall in downtown Berlin, Dr Paul Spiegel outlined the facts on the ground as reported by his organization, the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. As Deputy Director of the Programme Support and Management Division, he has a sound understanding of the magnitude of this growing challenge.

There are more than 19 million refugees spread across the world, almost half of which have been away from their home states for at least five years.

As these migrants begin to settle in host nations, becoming significant ethnic minorities in Jordan, Lebanon, Germany and Turkey, there is a growing need to present the benefits that these citizens bring to the new countries.

If the recent protests in Germany, or the anti-refugee rhetoric in Eastern European states have taught us anything, it’s that left unmanaged, sudden influxes of new migrants can create ethnic tensions.

People are concerned about sudden changes to the fabric of their states, and this is understandable. There will always be a desire to protect an existing standard of living, and without concerted efforts, that desire can manifest itself in unfortunate ways.

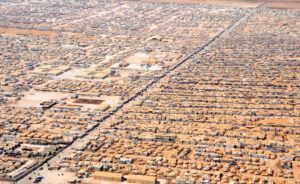

Za’atri refugee camp in Syria with an estimated population of 83,000 refugees (March 26, 2015)

Sharnoff’s Global Views/flickr

When the case for compassion is not articulated, when the benefits that refugees bring to a nation are not carefully explained, problems are bound to ensue. Indeed, this is why the talk was titled ‘Why refugees need jobs, bank accounts and insurance’.

Dr. Spiegel began by attempting to communicate this case. He began with a description of the key benefits that refugees bring to host nations, before painting a way forward for his organization in this.

Discussing the aging populations of Western Europe and the rest of the developed world, Spiegel spoke of the economic benefits that the predominantly young, working age refugees could bring to the continent. He spoke of Turkey and Jordan’s huge problems with participation in low skilled, informal work, pointing out that Syrians are beginning to take up these jobs ahead of domestic workers. This has led Turkish and Jordanian workers to find new jobs in higher-paid, formal sector jobs.

He noted that the regions that have hosted the majority of the Syrian refugees in these nations have also not experienced any additional increases in unemployment, suggesting that the provision of new, low cost labor has added a number of benefits to the economies receiving refugees, without imposing significant additional costs.

Perhaps the greatest evidence of this comes in the form of a recent report by the UNHCR, which found that 26 percent of new businesses registered in Turkey belonged to Syrian refugees, a staggering figure considering these new migrants still comprise less than three percent of the population.

Spiegel outlined his vision for these entrepreneurs, describing what his organization could do to support these new migrants. He spoke about the 15 percent of Syrian refugees who consider themselves artisans, outlining a plan for how the UNHCR could help foster a domestic craft industry for these people.

Work like this has been supplemented by new innovations in the provision of essential services to refugees. Unconditional cash transfers are perhaps the most exciting such field, where the UNHCR is seeking to provide new migrants with unconditional income support, rather than as food aid or conditional cash support.

The benefits of this kind of aid include a reduction in the cost of administration, greater choice for refugees who are given autonomy over their funds, and stimulus to the local economy. Not only does this last reason help refugees and host nations alike, but it also acts to combat negative perceptions in host nations that refugees are a drain on resources. Instead, it provides new migrants with an immediate opportunity to stimulate the local economy, and to begin a new life in their host nation.

Spiegel talked excitedly about how this new form of funding would allow refugees to progress from aid dependency, to self-sufficient, autonomous citizens. Indeed, a raft of studies seem to support his belief that this new form of aid will help lead recipients towards a better life.

He expressed this with optimism, reflecting on the desires that he had heard time and again from refugees in his work. People who expressed a strong distaste for handouts and instead, a longing for the opportunity to rebuild their lives again, to find work, a home and a new life in their new land.

He outlined a similar vision for the UNHCR’s approach to healthcare for refugees. The organization is looking to integrate emigrants into domestic systems so that fewer temporary care sites are required. Instead, it is hoped that refugees can become better integrated into the public services of their host nation, allowing them to commence a new life without waiting in temporary tent cities while their health is attended to.

Despite these new innovations, Spiegel was far from utopic about his organization. He was aware of its shortcomings, and the size of the challenge ahead. He argued that these solutions are not a panacea, but merely a starting point. With a global refugee total that is expanding at an alarming rate, we know that the current international system is not equipped to deal with these changes.

He reflected on the fact that current budgets for the UNHCR and the World Food Program have never been higher. Yet they are struggling to meet the same standard of service that they had previously delivered on smaller budgets.

Outlining his vision for the organization, Spiegel spoke of a more concerted effort on the part of the global community. He spoke of a need to do so, because not doing so was not an option. This is the kind of vision we need for a challenge of this scale.

We know that international cooperation is not enough, but we cannot succeed without it. We know that humanitarian aid is no panacea, but it is essential to overcoming this crisis. Ultimately, to succeed will require innovation beyond which we have yet managed to venture. It will require hard work, and human ingenuity. But that is still just the beginning.