Famous Senator John McCain asked a simple question when US General John “Mick” Nicholson Jr, the commander of Resolute Support Mission and U.S. Forces Afghanistan, testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee:

“Are we winning or losing?”

Nicholson responded that the war “is a stalemate” – an optimistic assessment given that the Afghan military is both rapidly losing control of its territory and suffering unprecedented casualties on the battlefield.

The general also said that he needs “thousands of more troops in order to carry out the mission he was assigned by President Obama”.

Although new president Donald Trump rarely mentioned the war as a candidate, he now must decide whether to continue or reverse his predecessor’s strategy of withdrawal.

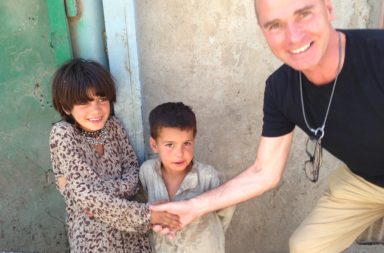

The impressive American officer comes from a military family. His father John W. Nicholson was a brigadier general in the army. He gave his son, who loves to read books about military history, the biography written by GLOBALO founder Dr Hubertus Hoffmann about his long-time mentor and Pentagon strategist Dr Fritz Kraemer. Read more about him here.

John William Nicholson, Jr. served as commanding general, Allied Land Command, and as the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division. On 4 February 2016, Nicholson was confirmed for a fourth star and to become General John F. Campbell’s successor as commander of Resolute Support Mission and U.S. Forces Afghanistan (USFOR-A).

Gen. Nicholson testified shortly after the release of quarterly statistics showing that the Afghan government now controls only 57 percent of the country, down from 72 percent a year earlier.

The general advised the Armed Services Committee that success in Afghanistan would entail the establishment of government control over “at least 80 percent” of the population.

Nicholson also delivered grim news about the heavy casualties that Afghan forces are suffering at the hands of the Taliban. After two consecutive years of unprecedented losses on the battlefield, the Afghans “have suffered almost twice as many casualties as [the U.S.] suffered in the previous 10 years.”

Gen. Nicholson made clear that success depended on the deployment of additional troops, an obvious point that senior officers could rarely acknowledge while President Obama remained in office.

While reporting that he had sufficient manpower to conduct counterterrorism missions, Nicholson estimated a “shortfall of a few thousand” trainers and advisers for Afghan forces. The general noted that NATO troops as well as American ones could help to fill this gap.

The shortfall of trainers and advisers is critical because a sustainable withdrawal of American forces depends on the readiness of Afghan troops to control and eventually defeat the Taliban. In his opening statement, Sen. McCain bitterly observed that Obama’s rush to hand the war over to the Afghans all but ensured the Taliban’s resurgence. “Time and again,” the chairman said, we saw troop withdrawals that seemed to have a lot more to do with American politics than conditions on the ground in Afghanistan.”

The political imperative to reduce American troop levels also led to other inefficient and self-defeating choices. For example, Nicholson explained, the pilots and helicopters of one combat aviation brigade from Fort Riley, Kansas deployed to Afghanistan without the uniformed mechanics who maintain their equipment. Instead, the Army spent “tens of millions of dollars” on civilian contract mechanics while “the soldiers who were trained to be mechanics are sitting back at Fort Riley” and don’t even have the chance to do the job they trained for. All in all, Nicholson said, there are two contractors for every American troop in Afghanistan.

Video February 1st, 2016

Going on Offense

“Offensive capability is what will break the stalemate in Afghanistan,” according to Gen. Nicholson. In December, Nicholson acknowledged that few Afghan troops were proficient enough to conduct offensive operations. While the Afghan army has 168,000 troops, 70 percent of offensive operations are conducted by special operators, who number only 17,000. In response to rapid Taliban gains on multiple fronts, Afghan authorities have shuttled their special forces around the country to deal with one crisis after another, leaving them exhausted. In his testimony, Nicholson announced a plan to almost double the number of Afghan special forces units over the next four years. There is a shortage of commandos right now, yet Nicholson explained, “You can’t produce these units overnight.”

The second critical offensive capability for the Afghans is the employment of air power to support troops fighting on the ground—what the U.S. military calls close air support. Last April, Afghan pilots flying the A-29 Super Tucano flew their first close air support missions. Gen. Nicholson reported that the eight A-29s in the Afghan fleet have already flown 800 missions. Another 12 planes are set to arrive by the end of 2018. Nicholson also asserted that the Afghans are also becoming more proficient at tactical air control and maintenance, so they won’t have to rely on the U.S. for those functions.

While improved striking power may help Afghan forces to manage the Taliban, it cannot resolve the internal failures that have weakened the both the military and the Kabul government. Nicholson testified that the Afghan army and national police include tens of thousands of “ghost soldiers” who exist only on paper, while corrupt officials pocket their salaries. The general identified corruption as the second most important cause – after “failures in leadership on the battlefield” – of the heavy casualties suffered by the Afghans in 2016.

Military strength is also no solution for dangerous divisions emerging in Kabul. For weeks, Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum has blocked police from arresting his bodyguards as part of an investigation into the alleged abduction and torture of a political rival. The vice president has also barricaded himself into a fortified compound in Kabul, raising the prospect of a debilitating split within government ranks.

Finally, offensive power cannot deprive the Taliban of the sanctuary they continue to enjoy in Pakistan, the support they receive from Iran, or the deepening ties they have to Russia. When pressed by multiple senators on how to change Pakistani behavior, Nicholson had little to offer except his agreement that the problem “needs to be at the top of the agenda” and that it requires the personal attention of the president and the secretary of defense. The general observed that Russia, like Iran, has begun to get involved in order “to undermine the United States and NATO.” As Nicholson’s testimony illustrates, Afghanistan is not a problem unto itself, but one that will require President Trump to think through the implications of his strategies for dealing with Russia and Iran as well.

Fifteen Years at War

At last week’s hearing, both Republican and Democratic senators expressed their frustration with a war that has lasted for 15 fifteen years, leaving Americans to ask why we are fighting at all. Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) raised the issue bluntly. “Could you just tell us in plain language,” Cotton said, “What are the American people – what are – you know, what are working folks out in Arkansas getting from more than 15 years of our presence in Afghanistan?” Nicholson answered that there are 20 terrorist organizations now operating in Afghanistan and Pakistan. American forces’ “number one goal [is] to protect the homeland from any attack emanating from the region.”

Sen. Cotton, who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan, followed up by asking about a potential to decision to withdraw our forces, sine 15 years is long enough. “Do you think that we would face the risk of an attack planned and directed from Afghanistan?”, the senator asked. Gen. Nicholson’s simple response was “Yes, Senator, definitely.”

The choice now facing President Trump is a deeply unpleasant one. He has announced his determination to stamp out radical Islamic terrorism, yet he has also made clear that he is tired of inconclusive foreign wars. Now he must decide whether to take responsibility for turning around an unpopular war, because there is no other way to ensure the defeat of terrorists determined to attack America.