Japanese banks Nomura and Daiwa recently indicated they are moving their EU base to Frankfurt and are applying for the appropriate regulatory licences. The announcements follow similar ones from Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, among others. Mitsubishi, however, seems to prefer Amsterdam and – oh, the irony – so does the largely UK-government-owned RBS.

With every announcement of this nature, up goes the cry that the UK’s finance industry will be crippled by Brexit as bankers flee, and European cities including Dublin and Paris, in addition to Amsterdam and Frankfurt, look to hoover up business. So, is London about to become emptied of its financial industry and will tumbleweed blow around the square mile? And why, then, are some banks (such as Wells Fargo) moving in.

In weighing up the argument between the camps that think the UK’s finance industry will be decimated against those who don’t, we need to sift through what is known, what is assumed and what can change. This includes how hard a Brexit it will be and whether or not the current government will survive, along with endless other questions.

What we know

What hasn’t changed is the location of the UK and its history as a financial centre. Yes, given its mid-way point between US and Asian markets and time zones, this is important. Thanks to its location and years of favourable policies, London has more international banks than any other city in the world. This scale gives London an edge over other European cities, and the fragmentation of financial centres to Dublin, Frankfurt and others, is undesirable.

It also hasn’t changed that the UK trades more dollars than anywhere else, including the US, and it also trades more Chinese yuan than anywhere else except Hong Kong. For now, the US dollar is the world’s most traded, and most important, currency. Many will argue that this position will ultimately be replaced by the yuan.

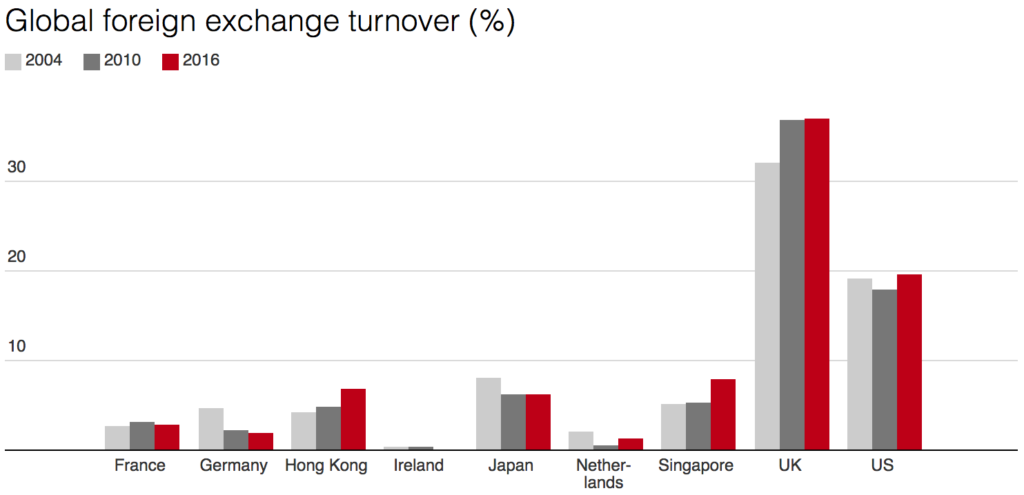

Moreover, London doesn’t trade just a little bit more than other financial centres, it trades almost double the amount of currency that is traded in New York and accounts for almost 40% of global trade. Any movement in the dominant position of London is likely to come from further east, with Hong Kong and Singapore leading that charge. Trading in the US dollar and euro are down while trading in the Chinese yuan and other Asian currencies is increasing rapidly, reflecting their increasing importance in global trade.

Losing membership of the EU may dent these figures, but what lies behind them is a significant amount of expertise and infrastructure that cannot simply be picked up and relocated in multiple cities. This means human capital that banks do not want to spread in different locations, assuming said human capital wishes to move.

Losing membership of the EU may dent these figures, but what lies behind them is a significant amount of expertise and infrastructure that cannot simply be picked up and relocated in multiple cities. This means human capital that banks do not want to spread in different locations, assuming said human capital wishes to move.

But it also includes the extensive infrastructure built by banks since the “big bang”, as the huge regulatory changes that took effect in 1986 are known and that saw the beginning of international banks move to London. This infrastructure includes the human elements, as banks need lawyers, insurance specialists, risk managers and the like. But it also includes the physical infrastructure. Increasingly important in this, is the cabling and IT equipment required for high frequency trading. Both Atlantic undersea internet cabling and local industry data centres well serve the UK and London.

Into the unknown

Nothing has actually changed yet (Brexit will not be official until April 2019). Moreover, the banks noted above (and others) are largely looking for office space. No one has jumped ship yet. These are contingencies you would expect any business to make when it is faced with the uncertainties surrounding soft vs hard Brexit – office space can get snapped up quickly.

London trades trillions in euros and has a large euro-denominated insurance industry. This is the currency most at risk, if the UK fails to secure post-Brexit passporting rights.

But a valid question is: can Europe handle this amount of trading? The answer is, currently, no. The infrastructure isn’t there. It appears as though the powers that be within the eurozone realise this. The pan-European Euronext exchange recently announced that it would extend its contract with the London Stock Exchange-owned LCH clearing house for a further ten years. The existing contract is due to expire in 2018. As part of the deal, some clearing may go through the Paris branch, perhaps enough to satisfy the ECB, but most will likely still be handled by its London headquarters.

Ultimately, the UK will lose some euro business. This is inevitable because the European Commission wants more euro denominated clearing to be under the auspices of the ECB. But the process will be slow. Even those banks looking at office space across the euro area are talking of staff moves in the low hundreds or less, not the many thousands.

Brexit will bring many challenges to the UK and its economy, from concerns about whether there will be enough labour to pick crops and staff hospitals to the costs that firms may face if trading outside the customs union. The list of uncertainties is long. But in terms of London’s financial centre, the bigger threat is likely to come from much further east.