U.S. Strategy and the War in Iraq and Syria

Iraq has just seen one of its most horrifying days of terrorism in what is now some thirteen years of war. ISIS has struck at Iraq’s civilian population with the clear goal of dividing the country between Sunni and Shi’ite—although one of its three bombs did kill Sunnis as well. The end result is at least 93 dead and hundreds of wounded—all innocent civilians.

ISIS’s Strategy of Mass Terrorism

To some extent, this reflects progress in the fighting. ISIS has lost a substantial amount of the territory it once controlled. While Iraq is anything but unified, it also has not seen the kind of divisions between Arab Sunni and Arab Shi’ite, or Arab and Kurd, that keep Iraqi forces from advancing in the west and gradually moving towards the liberation of Mosul. Using mass terrorist attacks against civilians to inflame the sectarian and ethnic fault lines in Iraq makes all too much sense from the perspective of ISIS—as do any such attacks that can provoke a response from Shi’ite militias against Iraq’s Sunnis, or divide its Arab and Kurds.

Moreover, repeatedly using terrorism to strike at civilian targets outside ISIS’s area of control is an effort to discredit the Iraqi government and create public demands to shift Iraqi security forces away from a focus on liberating Mosul and western Iraq to protecting the population. ISIS is attempting to distract attention from their own losses, to attract volunteers or funding, and to warn those in the areas it occupies just how ruthless ISIS can be if they oppose it. There is nothing irrational about ISIS’s actions from its ideological perspective and values. They have a solid strategic rationale.

Reacting to Real ISIS Losses

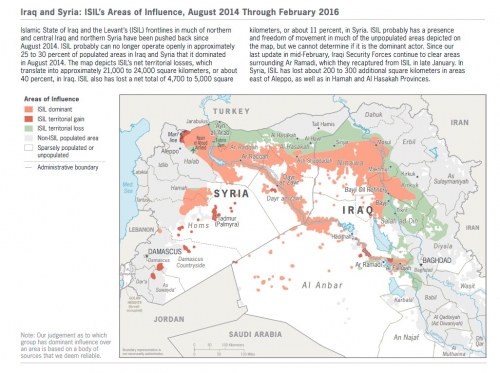

There is no doubt that the Iraqi government, militia, and tribal forces—as well as Syrian Kurdish and Arab rebel forces—have made gains against ISIS. Maps and claims differ, and official U.S. statements often make absurd claims about liberating large areas of empty desert. In broad terms, however, the most recent map on the Department of Defense website—which is shown in Figure One below—does reflect legitimate gains.

Figure One: U.S. Department of Defense Map of ISIS Losses as of February 2016

In fact, the map understates the gains made since February, which include a major ISIS defeat and its loss of Palmyra. This is shown in Figure Two, which displays a BBC map of areas of ISIS control in Iraq and Syria as of April 26, 2016—some two months later. This map draws upon the consistently excellent work of the Institute for the Study of War, as well as USCENTCOM, and also highlights the impact of the U.S-led air campaign and the real world difference between ISIS control of populated areas and its freedom to operate in largely unpopulated desert.

Figure Two: ISIS Areas of Control in Syria and Iraq as of April 26, 2016

The Price of a U.S. Strategy of Creeping Incrementalism

The problems the United States and its allies face, however, do not lend themselves to anything approaching as simplistic an approach to strategy as the one chosen by ISIS. These are issues that James Clapper, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, raised in part in his May 10 interview with David Ignatius in the Washington Post, and where the Obama Administration needs to provide a far clearer picture of both its strategy and actions than it has provided to date.

Clapper addressed several aspects of the grim reality that the United States is now forced in many ways to try to find the least bad options under very difficult circumstances. First, he said that, “They’ve lost a lot of territory…We’re killing a lot of their fighters. We will retake Mosul, but it will take a long time and be very messy. I don’t see that happening in this administration.”

This statement seems to have come as a surprise to some commentators, but it should have been all too obvious a reality. The Obama Administration did not act decisively at the points in the conflict when it might have prevented a long war of attrition, and its real world “strategy” in both Syria and Iraq has been one of slowly escalating U.S. involvement in what amounts to creeping incrementalism. It has been far too slow to provide an adequate train and assist mission to rebuild the half-finished Iraqi Army that Iraq’s former Prime Minister—Maliki—effectively corrupted and destroyed in his search for power and control after U.S. forces left at the end of 2011.

Only now do U.S. Special Forces, Marine Corps fire support units, and other elements of U.S. forces seem to be large enough to begin providing the level of forward presence and support to Iraqi combat forces that can help them be effective and make proper use of Coalition air support in the less populated areas of western Iraq. Even now, the level of U.S. support and willingness to provide it close enough to actual combat remains uncertain.

The United States now seems to have some 4,500 “boots on the ground”—the kind of U.S. train and assist forces that are the only hope for creating effective Iraqi forces. That being said, there is no clear picture of where they are, what they are doing, or their actual numbers—in part because the United States disguises the totals for security reasons and in part because it is playing political games to under report such forces by not including some that it claims have limited tours of duty.

Mosul and Iraq’s Military Progress

Iraqi forces remain deeply divided between regular government forces, largely Shi’ite Popular Militia Forces, and Iraqi Sunni tribal forces. Leadership, arms, supply, and the ability to concentrate are still developing. Their ability to reinforce and resupply in combat is still very poor and sometimes crippling. Far too many represent rival powerbrokers, ethnic groups, and sects. Many are only in uniform because this is the only source of income for many young men in a country with an underdeveloped and shattered economy, a horribly corrupt and self-seeking government, and whose central government and Kurdish areas are now effectively bankrupt because of cuts in oil prices and export revenues.

This is not yet force that can liberate Mosul. Nor can they liberate the more heavily populated areas in northwest Iraq that involve radically different kinds of urban and built-up area warfare, massive civilian populations. These are areas that ISIS can transform into fortresses of booby-trapped buildings, concentrations of civilian hostages and human shields, and lines of sudden or surprise suicide attacks. It can turn towns and cities into unoccupiable rubble, destroy infrastructure, and constantly carry out attacks on Iraqi rear areas and troop concentrations from the desert.

Unless ISIS is defeated in both Syria and Iraq, it also presents the problem that Iraqi forces will liberate the equivalent of rubble that they cannot defend from ISIS forces and ratlines to the west. ISIS can use terrorism to both try to provoke clashes between Sunni and Shi’ite forces and Arab and Kurd, as well as repeat the kind of terrorist attacks in other portions of Iraq that it has just used in Baghdad.

Victory Means Civil-Military Victory and Only Iraqis Can Win the Civil Victory

It is equally impossible to “win” in a nation that is crippled at the civil level. Here, Clapper’s second major comment is all too relevant: “I don’t have an answer…The U.S. can’t fix it. The fundamental issues they have—the large population bulge of disaffected young males, ungoverned spaces, economic challenges and the availability of weapons—won’t go away for a long time…Somehow the expectation is that we can find the silver needle, and we’ll create ‘the city on a hill’…That’s not realistic, because the problem is so complex.”

Clapper was not in any sense saying that the fight was hopeless. He was not saying that victory was not possible. He was pointing out another aspect of the search for the least bad option. No military victory in Iraq can provide lasting results unless Iraqis create their own formula for political unity, for economic development and sharing the nation’s wealth, and for ending the patterns of waste and corruption that destroy the nation’s hopes for real progress. Prime Minister Abadi, Iraq’s technocrats, and some of its politicians actually do serve their country.

Far too much of Iraq’s elite, however, serve only themselves or a given sect or ethnic group. They are at least as much of an enemy to their country as ISIS. Until they change—or are force out of power—no military success can rescue a nation whose political and civil leaders have turned it into a failed state. It is also all too clear that these changes must come from within Iraq and cannot be forced from the outside. As the United States has seen in Afghanistan and during its earlier occupation of Iraq, the United States and other outside states cannot reshape a nation. The civil side is always as important as the military side—and Iraq must take responsibility for helping itself.

The Syrian Dimension

This raises the issue of Syria. The Obama Administration has made other major strategic mistakes that now condemn it to choosing between least bad options. One is that it tried to pursue an “Iraq first strategy” when it was always clear that ISIS occupied critical areas of both Iraq and Syria, and western Iraq could never be secured unless ISIS was defeated in eastern Syria.

Another is that it placed its strategic focus on ISIS, and not on the broader threats created by steadily growing the civil war between the Assad regime and Arab rebel forces, and Kurds in Syria; and the constant risk of similar fighting between Iraq’s Arab Shi’ites, Arab Sunnis, and Kurds.Figure One and Figure Two tell only part of the story.

The real fighting in Syria involves four major groups of factions: ISIS, Assad’s supporters, Syrian Kurds, and some 40 or more factions of Arab Sunni rebels which range from “moderates” to supporters of Al Qaida. Iraq is divided into ISIS, Sunnis that dominate some parts of western Iraq, but also make up large part of the population of Baghdad and areas in the east, Kurds that now occupy roughly twice the area they did before the U.S. invasion in 2003, and Shi’ites that are largely in the East.

Figure Three and Figure Four tell only part of this story and sharply distort the real ethnic and sectarian boundaries in Syria and Iraq. They do, however, make it brutally clear that a strategy for ISIS is only part of the story and the defeat of ISIS alone will only be a prelude to new problems and conflicts.

Figure Three: Institute for the Study of War Estimate of the Conflicting Zones of Control in Iraq

Figure Four: New York Times Estimate of the Conflicting Zones of Control in Syria

In addition, power—like nature—abhors a vacuum, and outside powers would pursue their own strategies independent of the United States. The United States never fully came to grips with the fact Iran and Hezbollah played a major role in Syria, and had acquired more influence in Iraq by the time U.S. forces returned than that which the United States possessed.

The United States did not take account of the broader Arab resistance to an Assad and Alawite controlled regime fighting Sunnis in Syria, and Shi’ite-Iranian dominance in Iraq. President Obama still does not seem to understand why Arab Sunnis do not have the same strategic focus on ISIS as the United States and Europe. He truly does not seem to understand the depth of the tension between Iran and its Arab neighbors, and the extent to which this shapes Arab strategic priorities. This is exemplified by his comments quoted in the now famous Atlantic article that implied the Saudis were freeloading on U.S. power. Really, when they have recently spent some 13% to14% of their GDP on military forces while the United States spends well under 4%?

The United States failed to pay full attention to Turkey’s decades-long struggle against its Kurds, its fear of the political and military emergence of Syria’s Kurds, and its fear of some broader Iraqi Kurdish support of separatism that would involve Turkey’s Kurds as well.

Finally, it is unclear that the United States ever seriously considered the possibility of Russian intervention in Syria—until it happened. The Russian reaction to events in Libya and what it called U.S. support of “color revolutions” in an effort to dominate new countries in the Middle East. Putin’s reaction to NATO and EU expansion into former Soviet-dominated areas, U.S. and European treatment of Russia’s intervention in the Ukraine, NATO’s added activity in Poland and the Baltic states, and Russia’s reaction to U.S. inaction in Syria—its one remaining “base” in the Middle East—did not necessarily make Russian intervention in Syria seemprobable, but they certainly made it possible. At least to date, however, no one has argued that the United States had any contingency plan.

A U.S. Strategy or a Poison Pill for the Next Administration: ISIS and After ISIS

It is striking that the U.S. Department of Defense published a diagram of its strategy in Iraq and Syria for the first time on its web site that clearly links Iraq and Syria. This diagram is shown in Figure Five. It scarcely, however, describes a strategy for dealing with ISIS, much less the far broader issues in Syria and Iraq.

Figure Five: The Department of Defense Diagram of U.S. Strategy Against ISIS

This raises a far more critical issue about the future. The United States now faces least bad options that are almost certainly far worse than when the Obama Administration began its military interventions in Syria and Iraq. Acting incrementally and indecisively has its costs—just as acting too quickly and decisively, and without proper analysis and planning, did in the case of the previous administration. The question remains, however, does the Obama Administration have any real strategy to deal with the least bad options it still has, the challenges raised by DNI Clapper, and the issues outlined in this analysis? Or, is it still largely reacting to events and riding out its time in the office?

It is not enough to focus on ISIS or even to defeat it. It is not enough to buy time by negotiating a limited ceasefire or cessation of hostilities in Syria. A functional strategy must also look beyond the military dimension and recognize the equal importance of the civil dimension in Syria and Iraq—and must deal with the interests and role of key outside actors like Turkey, Russia, Iran, and the Arab states. The administration must look beyond tactics and immediate problems and at least set clear grand strategic goals.

There is a vital difference between making the best possible coherent effort in the face of extraordinarily difficult circumstances, and handing the next administration the equivalent of a “poison pill.” This is particularly true when the Administration’s legacy now seems likely to be even worse in Afghanistan, Libya, and Yemen. The Bush Administration almost certainly should have equal blame for many critical mistakes, but sixteen years of failed leadership is not an excuse for eight.