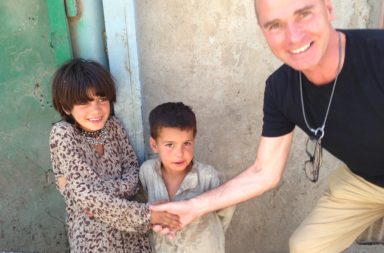

“I was able to buy whatever I needed while I was cultivating poppy right after Taliban’s regime collapsed,” says Amanullah, a farmer from the Northern Balkh province in Afghanistan. He adds, “I am not satisfied by my government, because they don’t let us cultivate poppy anymore while farmers are freely cultivating it in the south of the country, isn’t it a paradox?”

Amanullah is just one example of out of thousands Afghan farmers who used to earn considerable amounts by cultivating poppy, mostly during and after the Taliban regime.

The farmers say that poppy plants grow bigger and faster and they earn more from them compared to other plants. This could be one of the major reasons for the large poppy cultivation in the country.

Afghanistan is known to be the greatest illicit opium producer in the world. In addition to opiates, this country is also the largest producer of Cannabis (mostly hashish) in the world, although a fatwa (religious judgment) was issued by Muslim clerics claiming that opium production is in contrary to the Sharia law.

In 2014, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) poppy cultivation reached a record breaking high in Afghanistan. The report outlines that the total cultivation area was about 22400 hectares which constitutes a 7% increase compared to 2013! Preventative measures were undertaken by a number of Afghan and Non-Afghan Counter-Narcotics Organizations since the removal of Taliban in 2001. The US has spent over 7 billion USD to eradicate poppy farming, however, most of the money seems to have gone into the pockets of the Taliban and local warlords.

To counteract the drug trafficking, Afghanistan’s government has attempted to arrest several well-know drug traffickers. So far with limited success and it would seem that foreign support is much needed in these matters.

Why Afghanistan?

There are several reasons why it usually failed to eradicate poppy in Afghanistan; the two followings are the major reasons why poppy is soared in this country:

1. Corruption in the administration of Afghanistan

2. Lack of security

Experts say that a much broader approach is needed to combat poppy farming .Otherwise it is hard to prevent it when a large number of people are addicts.

80 percent of the global opium production is supplied from Afghanistan’s Helmand province; the province is known the South Asian Nation’s largest opium-producing province. There are an unusually high amount of Taliban fighters there and thus it is a challenge for central government to combat the poppy farming there.

In the northern province of Balkh, where opium cultivation is said to have collapsed to zero, there is evidence that farmers have turned to hashish instead and the number of hashish smokers is on the rise. So the move away from poppy has sadly not been for the better.

Providing alternative livelihoods

The development of alternative livelihoods for Afghan poppy growers is an important element of current counter-narcotics strategy, which includes an incentive scheme known as the ‘Good Performance Initiative‘, set up to reward villages for moving away from opium. The scheme argues that because other crops often face pitfalls such as the absence of distributors, domestic demand or consistent prices abroad, the international community should help Kabul to set up an agency, modeled on the Canadian Wheat Board, that would purchase crops from farmers at consistent prices, and market and distribute them internationally. While Afghan farmers will not receive substantial income from cultivating saffron it could be a good alternative to poppy. Some provinces like Herat have already switched to growing it and have witnessed positive results.

In 1974 a different approach was undertaken by the US in Turkey. They began licensing poppy cultivation for the purpose of producing morphine, codeine, and other legal opiates. Legal factories were built to replace the illegal ones. Farmers registered to grow poppies, and they paid taxes.

Why not add Afghanistan to this list? The only good arguments against doing so—as opposed to the silly “it just doesn’t work like that” arguments—are technical: the weak or nonexistent bureaucracy will be no better at licensing poppy fields than at destroying them, or that some of the raw material will still fall into the hands of the drug cartels. Ultimately the key is to seriously reform the corrupt bureaucracy and legalize part of the poppy production.