As Emmanuel Macron gears up for a battle over plans to reform the French labour market, it is essential that he does not diminish France’s strong system of support for the unemployed. Instead, Macron’s government should be expanding support for the most disadvantaged unemployed people, particularly the young.

On August 31, Macron’s prime minister, Edouard Philippe, announced details of five decrees that will introduce reforms to labour laws and increase job flexibility. Although some trade union leaders have been working with the government on the plan, strikes are planned on September 12.

Muriel Pénicaud, the French minister of labour said the reforms are only the first of many planned by Macron to tackle unemployment and that she would soon begin consulting on reforming the French unemployment insurance system. A confrontation is already forming regarding cuts to emplois aidés, jobs for the unemployed in the public and private sector for which employers receive state subsidies.

When it come to unemployment support, Macron’s party, En Marche, states some of its key policy aims as fighting unemployment and ensuring that work enables people to escape poverty. Proposals so far include raising the prime d’activité – a benefit offering financial support to workers on low incomes – and extending unemployment benefits to workers who have resigned.

But in late August, Philippe announced that the number of subsidised jobs will fall by over half in 2018 compared to 2016. Created in 1980 in a context of high unemployment, these jobs were designed to reduce unemployment, particularly among disadvantaged young people. The contracts have been rebranded with different names over the years but the aims have remained similar. The number of people employed on such contracts increased under François Hollande, Macron’s predecessor, but the new government contends that they are inefficient and too costly.

COORACE, a federation of social enterprises, wrote to Macron criticising the reduction in subsidised job contracts. It argues the move risks severely damaging the voluntary sector, which has traditionally employed many people on such contracts, and could harm opportunities for disadvantaged job seekers and young people. Mayors from across France have also expressed serious concern regarding the impact of the cuts on their administration.

A generous safety net

France has an unemployment support system that is relatively strong at protecting job seekers, particularly those who have previously been in work. It is among the developed countries that spend the most on active labour market policies, which aim to move unemployed people into work.

In 2013, the French state spent 0.87% of its GDP on policies such as training, unemployment benefits and employment incentives. While lower than the level spent by Sweden, at 1.35% of GDP, it was considerably higher than Germany’s 0.67% or the UK’s 0.23%. France’s generous social safety net is effectively paid for by the country’s relatively high levels of productivity.

The exact amount that unemployed job seekers in France receive each week depends on their personal circumstances. Research in 2016 found unemployed people in France were offered 60-75% of their previous salary for between 16 and 52 weeks. For comparison, in the UK there is a flat rate of £57.90 per week for 18 to 24-year-olds, and £73.10 for those over 25.

As part of my own PhD research, I interviewed 19 out-of-work couples with children under the age of 13 in Lille, northern France, and 19 couples in a similar situation in Sheffield, northern England. I found that the greater investment in unemployment support in France than the UK clearly affected the couples’ experience.

Beneficiaries of the RSA – the main minimum income programme in France for those aged 25 or over, unemployed or on a low salary – told me that they benefited from reactive and personalised support. The French couples generally described strong relationships with their advisers:

Whenever I want something, whatever it is, she is there … I get things off my chest … We explain things, we talk, we laugh … If I need to do a CV or whatever it is, I go to see her and she knows how to do it.

By contrast, couples in the UK who were claiming Jobseekers’s Allowance – a benefit supporting unemployed people or those working below 16 hours per week – reported greater tension with their advisers. The French couples also reported being enrolled on longer-term, more comprehensive and more personalised training schemes than parents in the UK.

Jobs for the young

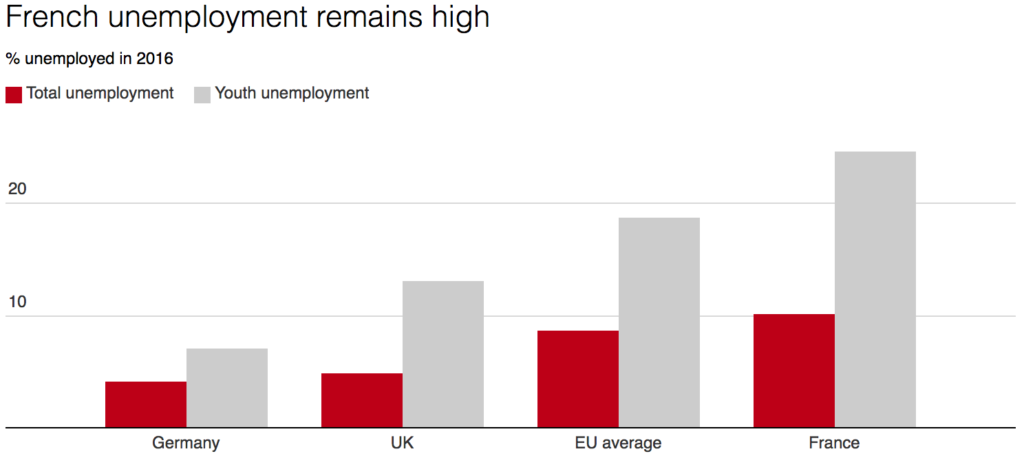

Despite the level of support, unemployment remains a challenge in France. In 2016, the overall unemployment rate in France and the rate for 15 to 24-year-olds were both well above EU averages – as the graph below illustrates.

Macron’s election is an opportunity for the French government to address the reasons behind persistently high unemployment in France. But policies should focus on the most disadvantaged unemployed people, particularly the young.

Macron’s election is an opportunity for the French government to address the reasons behind persistently high unemployment in France. But policies should focus on the most disadvantaged unemployed people, particularly the young.

Perhaps the French government should consider extending the budget of the Missions Locales, local employment centres across France that aim to accompany young people aged 16-26 and to provide them with personalised support to find work. These centres, which receive government and EU funding, have been found to achieve impressive results in helping disadvantaged young people into employment, but suffer from financial instability.

Macron’s attempt to liberalise the French economy by making it easier to hire and fire employees may reduce some of the reluctance among French firms to take on young people. But it is not yet clear that his government plans to do enough to address the wider barriers affecting youth unemployment. In 2016, the IMF argued that France was suffering from a skills mismatch which appears to have worsened since the global economic crisis.

It is still early to judge Macron and Philippe’s policies on unemployment, but so far their proposals do not go very far in helping France’s most disadvantaged job seekers. Indeed, cuts to the unemployment insurance system as well as the number of subsidised jobs could lead to a rise in unemployment.