For students of architecture who visit to India, a trip to the Taj Mahal is a must. For aficionados of ice cream who visit India a stop at Mumbai’s Taj Ice Cream is just as important. Opened it 125 years ago, Taj Ice Cream sought to bring what was then a treat usually served to India’s colonial rulers to the masses. While the handmade ice cream at Taj Ice Cream has changed little since that time, the Bhendi Bazaar where it is located is undergoing a colossal redevelopment project one that could have important ramifications on India and other informal communities elsewhere.

Bhendi Bazaar is a small mostly Shia Muslim ghetto in a large mostly Hindu city. Taxis often refuse to venture down the narrow alleys of the bazaar where foot traffic and the odd daring motorbike dart through the thousands of informal vendors and neighbourhood boys playing cricket in the shadows of the areas aged four story apartments. Here friendly street vendors sell everything from car parts to CDs and cellphone products, cookware, capsicum. The Saifee Burkhani Upliftment Trust (SBUT) a Shia religious endowment hopes to redevelop this area that will replace the ghetto with a Dubai like district of glistening multi-story towers.

Supposedly those in the know can purchase dangerous pets and endangered species here, but the most dangerous species I encountered was a billy goat very much annoyed at my presence. As I past a shop selling antiques (some dating to British colonial times a large goat stepped out from behind a low stall and instantly locked eyes with me ignoring the dozens of other presumably more familiar faces. The goat, offended by appearance, charged at me at full speed, his gnarled horns aimed at me. His hooves slipped just for a moment on the oily pavement allowing me to side-step his Quixotic charge behind a parked car. Figuring the issue was over I proceeded but, soon a small boy yelled behind me alerting me to another charge. My caprine opponent and I replayed our matador routine, this time a parked motor scooter served cover. At this point a teen jumped off a low-stoop nearby taking the goat by the horns and telling me he would hold it until I had passed. I thanked him and took one last photo of the scene as I turned a corner to reach my destination: Taj Ice Cream.

Taj Ice Cream’s storefront is so non-descript I walked past it. Yet here lies a frozen treat so special that Conde Naste has gushed about it and celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain made a pilgrimage here. It is even mentioned in the Guinness Book of Records apparently. Its iconic ice cream is prepared in large batches and served in weddings across the city.

The joint was originally known as Saraf Ali’s Ice-cream when it was established by Tayyab Ali Icecreamwalla in the late 1880s (The family took the name of the business as their last name). Tayyab’s son Saraf Ali next inherited the business and the name was changed at some point to the catchier Taj Ice Cream. The place is now owned by Saraf Ali’s sons Abbas, Hatim and the youngest Yousuf.

The day-to-day operations are handled by Moustafa Abbas, who tells me he is the fifth generation of the Icecreamwalla family to work in the shop. The shop initially focused on fruity flavors but, Mustafa has tried update the shop with new flavours introducing gooseberry, roasted almonds, chocolate, and even more exotic flavors. I noted paanmasala, a mild narcotic but it was apparently out of stock.

Moustafa explains that while the shop has perfected recipes for some 50 flavours, most are only seasonal. Still he insists his shop can make flavours to order, “There is no limit to the ice creams and fresh fruit combination we can have for you. Tell us in the afternoon what flavors you want and we will have it for you the next morning.” Devotees of Taj Ice Cream have debate which of Taj’s flavours are the best with both strawberry and mango having strong partisans. When asked Moustafa comes down firmly in defence of his alphonso mango. Some of the more exotic flavors are just as good such as sitafal (custard apple) which is not too sweet and has just a hint of fruity chalkiness which gives proof that the treat is made from fresh fruit.

Flavors aside Moustafa emphasises that ice cream there is still made the same way. Mustafa speaks with passion about the low-tech way of making ice cream. “You have to hand crank ice cream, otherwise ice cream just has too much air if it is made a machine.” The milk is boiled before use, there is no modern refrigeration, there is no electricity save for a light panel overhead. During my visit a near shirtless sexagenarian man demonstrated how the ice-cream is hand cranked early each morning and stored in ice boxes. By nightfall the ice cream is sold-out the process repeats itself each day. Though occasionally afternoon batches are made to order. Mustafa says some of the employees come from families who have worked there for generations.

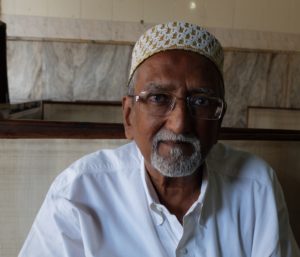

On a lazy afternoon Moustafa is minding the till when the elderly Youssouf Icecreamwalla stops by. The elderly Youssouf is as animated as a Disney character and is eager to speak to the foreign visitor in his shop. His chopped English seem like the dialogue from a Rudyard Kipling story. Running out of English words, Hassan translates for Yousuf. Yousuf’s points out on wall the only decoration in the simple restaurants: A picture of the late religious leader Mohammed Burhanuddin. Born March 6, 1915 Burhanuddin was the 52nd Dai or leader of the al-Mutlaq of Dawoodi Bohras, a subgroup of Shia Ismaili Muslims with roughly a million adherents worldwide. Yousouf wears the distinctive white cap with gold trim that was mandated by Burhanuddin’s faithful.

Burhanuddin sought to preserve identity of the unique community. He mandated a distinctly Muslim dress (though a walk through Bhindi Bazaar suggest a somewhat lax application). The Dawoodi Bohras in Mumbai are the descendants of Yemeni traders. Over half of the sects members live in South Asia. This sect of Ismaili Shia had long used Lisan al-Dawat a dialect of Gujrati with Arabic, Urdu and Persian as a liturgical language. Under Burhanuddin an effort was made to popularize it for everday use. Under Burhanuddin community kitchens were built in Mumbai to allow more women free to spend time in education and professional pursuits. A consulting services was also mandated by the Dai to help business owners.

The former Dai announced his most ambitious plan in 2009 when he sought to redevelop and modernize Bhindi Bazar. Burhanuddin’s plan included uprooting nearly 20,000 people and 1,250 businesses. The four story buildings built by the British in the late 19thcentury for workers flooding into the city would be replaced series of modern 17-story towers. These were to be environmentally friendly with solar panels, shady parks, run-off water storage and ample parking. The planned commercial zones will tower over surrounding neighbourhoods. If the plan looks a lot like Dubai and that’s because it was crafted with input with some of the same consultants. Firms like Deloitte, KPMG (India), Perkins Eastman International (New York) have all worked as consultants on the project.

India is the world’s largest democracy with a bureaucracy to match. In 1947, following socialist policies enacted strict rent control. Today some tenants in Bhendi Bazaar pay 200 rupees, a figure that has been well below the maintenance costs for years. The government is watching the Saifee Burkhani Upliftment Trust plan closely to see if the planned urban renewal is a success.

Half of the people in Mumbai live in slums with internment access to utilities and transport and previous development plans for the city have stalled. In 1997, the local government announced that Dharavai, one of the largest slums, would be redeveloped. By 2008, so little has changed the area was used as a setting for the Hollywood film Slumdog Millionaire. In the eight years since, improvements have been halting. The world’s first slum museum was set up in Dharavai in January of this year.

The Dai’s temporal and spiritual authority is hoped to be enough to move the Bhindi Bazaar project forward. A visit there finds demolished buildings and evidence of construction activity. Some 70% of the people in the area and an equal number of business owners are Dawoodi Bohras. Yosuouf Icecreamwalla is an enthusiastic supporter to replace the colonial era though he is unsure what it will me for Taj Ice Cream but, the new facilities will improve hygienic conditions for the thousands who live in the area. Those relocated due to the renovation are being housed for free in new homes but, whether they will be able to afford rent in the new Bhindi Bazaar is unclear but, the trust has vowed to work with the community to preserve its character.

Burhanuddin died in January 2014 at the age of 98. His death has lead a secession battle for his throne that has divided families and marriages over the question of who will be the next Dai. Mufaddal Saifuddin who emerged as the recognized head of the sect and of the Saifee Burhani Upliftment Trust behind the development. Given the turmoil over the new Dai, nostalgia for the old guy is not hard to find.

In another part of Bhindi Bazaar, Hassan who works in a machine shop takes a moment to sit in the shade in the 40 degree weather. He has spent all day under the of hulk of a Japanese mini-van he is salvaging it parts. Motor oil stains dot the pavement. He encourages me to take photos when I pass. I soon notice a photo of the previous Dai in the back of his shop. I ask about the plans for the area, is the new Dai up to the challenge? “ We will see, they have big plans for all us. But, I’m not sure what the business will do with all the construction and dust.” Not everyone has accepted the relocation plan and holdouts remain.

Efforts to bring modern urban planning to this part of “Bombay” have a long history. On the edge of Bhindi Bazaar is the Crawford market which opened in 1882. It was the first structure lit with electricity in India. Just inside the entrance is a frieze designed by John Lockwood Kipling, father of author Rudyard Kipling. The younger Kipling grew up a 10 minute walk away from the market at what is now the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art. The home where Rudyard Kipling (though substantially rebuilt over the years) sits on the campus.

When it was built Crawford Market symbolized everything about what the British hoped to bring to India: modernity and order. The area behind the market or “Behind the bazaar” was forgotten. Overtime “Behind the bazaar” morphed into the Indian sounding Bhendi Bazaar. Back at the ice-cream shop Moustafa is also positive about the move and the areas future. “We have been in the same location here since the beginning. No matter how the Bazar changes we will serve the same ice cream. This is our identity” Moustafa explains as the sound of the hand cranking of ice cream mixes with the engine noise of a small motorbike overcrowded with cartons of Coca-Cola products.